Playing to Win, Part 1

I wrote this article many years ago. It was so widely quoted and valuable to so many that I spent two years writing the book Playing to Win. The book is far more polished than these articles, better organized, and covers many, many additional topics not found on my site. If you have any interest in the process of self-improvement through competitive games, the book will serve you better than the articles.

Playing to Win, Part 1

Playing to win is the most important and most widely misunderstood concept in all of competitive games. The sad irony is that those who do not already understand the implications I'm about to spell out will probably not believe them to be true at all. In fact, if I were to send this article back in time to my earlier self, even I would not believe it. Apparently, these concepts are something one must come to learn through experience, though I hope at least some of you will take my word for it.

Introducing...the Scrub

In the world of Street Fighter competition, there is a word for players who aren't good: "scrub." Everyone begins as a scrub---it takes time to learn the game to get to a point where you know what you're doing. There is the mistaken notion, though, that by merely continuing to play or "learn" the game, that one can become a top player. In reality, the "scrub" has many more mental obstacles to overcome than anything actually going on during the game. The scrub has lost the game even before it starts. He's lost the game before he's chosen his character. He's lost the game even before the decision of which game is to be played has been made. His problem? He does not play to win.

This dog may be playing poorly, but at least he still has his nonsensical internal code of honor.

The scrub would take great issue with this statement for he usually believes that he is playing to win, but he is bound up by an intricate construct of fictitious rules that prevent him from ever truly competing. These made-up rules vary from game to game, of course, but their character remains constant. In Street Fighter, for example, the scrub labels a wide variety of tactics and situations "cheap." So-called "cheapness" is truly the mantra of the scrub. Performing a throw on someone often called cheap. A throw is a special kind of move that grabs an opponent and damages him, even when the opponent is defending against all other kinds of attacks. The entire purpose of the throw is to be able to damage an opponent who sits and blocks and doesn't attack. As far as the game is concerned, throwing is an integral part of the design--it's meant to be there--yet the scrub has constructed his own set of principles in his mind that state he should be totally impervious to all attacks while blocking. The scrub thinks of blocking as a kind of magic shield which will protect him indefinitely. Why? Exploring the reasoning is futile since the notion is ridiculous from the start.

You're not going to see a classic scrub throw his opponent 5 times in a row. But why not? What if doing so is strategically the sequence of moves that optimize his chances of winning? Here we've encountered our first clash: the scrub is only willing to play to win within his own made-up mental set of rules. These rules can be staggeringly arbitrary. If you beat a scrub by throwing projectile attacks at him, keeping your distance and preventing him from getting near you...that's cheap. If you throw him repeatedly, that's cheap, too. We've covered that one. If you sit in block for 50 seconds doing no moves, that's cheap. Nearly anything you do that ends up making you win is a prime candidate for being called cheap.

Doing one move or sequence over and over and over is another great way to get called cheap. This goes right to the heart of the matter: why can the scrub not defeat something so obvious and telegraphed as a single move done over and over? Is he such a poor player that he can't counter that move? And if the move is, for whatever reason, extremely difficult to counter, then wouldn't I be a fool for not using that move? The first step in becoming a top player is the realization that playing to win means doing whatever most increases your chances of winning. The game knows no rules of "honor" or of "cheapness." The game only knows winning and losing.

A common call of the scrub is to cry that the kind of play in which ones tries to win at all costs is "boring" or "not fun." Let's consider two groups of players: a group of good players and a group of scrubs. The scrubs will play "for fun" and not explore the extremities of the game. They won't find the most effective tactics and abuse them mercilessly. The good players will. The good players will find incredibly overpowering tactics and patterns. As they play the game more, they'll be forced to find counters to those tactics. The vast majority of tactics that at first appear unbeatable end up having counters, though they are often quite esoteric and difficult to discover. The counter tactic prevents the first player from doing the tactic, but the first player can then use a counter to the counter. The second player is now afraid to use his counter and he's again vulnerable to the original overpowering tactic. (See my article on Yomi layer 3 for much more on that.)

Notice that the good players are reaching higher and higher levels of play. They found the "cheap stuff" and abused it. They know how to stop the cheap stuff. They know how to stop the other guy from stopping it so they can keep doing it. And as is quite common in competitive games, many new tactics will later be discovered that make the original cheap tactic look wholesome and fair. Often in fighting games, one character will have something so good it's unfair. Fine, let him have that. As time goes on, it will be discovered that other characters have even more powerful and unfair tactics. Each player will attempt to steer the game in the direction of his own advantages, much how grandmaster chess players attempt to steer opponents into situations in which their opponents are weak.

Sometimes I just don't know what to say.

Let's return to the group of scrubs. They don't know the first thing about all the depth I've been talking about. Their argument is basically that ignorantly mashing buttons with little regard to actual strategy is more "fun." Superficially, their argument does at least look true, since often their games will be more "wet and wild" than games between the experts, which are usually more controlled and refined. But any close examination will reveal that the experts are having a great deal of fun on a higher level than the scrub can even imagine. Throwing together some circus act of a win isn't nearly as satisfying as reading your opponent's mind to such a degree that you can counter his ever move, even his every counter.

Can you imagine what will happen when the two groups of players meet? The experts will absolutely destroy the scrubs with any number of tactics they've either never seen, or never been truly forced to counter. This is because the scrubs have not been playing the same game. The experts were playing the actual game while the scrubs were playing their own homemade variant with restricting, unwritten rules.

The scrub has still more crutches. He talks a great deal about "skill" and how he has skill whereas other players--very much including the ones who beat him flat out--do not have skill. The confusion here is what "skill" actually is. In Street Fighter, scrubs often cling to combos as a measure of skill. A combo is sequence of moves that are unblockable if the first move hits. Combos can be very elaborate and very difficult to pull off. But single moves can also take "skill," according to the scrub. The "dragon punch" or "uppercut" in Street Fighter is performed by holding the joystick toward the opponent, then down, then diagonally down and toward as the player presses a punch button. This movement must be completed within a fraction of a second, and though there is leeway, it must be executed fairly accurately. Ask any scrub and they will tell you that a dragon punch is a "skill move." Just last week I played a scrub who was actually quite good. That is, he knew the rules of the game well, he knew the character matchups well, and he knew what to do in most situations. But his web of mental rules kept him from truly playing to win. He cried cheap as I beat him with "no skill moves" while he performed many difficult dragon punches. He cried cheap when I threw him 5 times in a row asking, "is that all you know how to do? throw?" I gave him the best advice he could ever hear. I told him, "Play to win, not to do ˜difficult moves.'" This was a big moment in that scrub's life. He could either write his losses off and continue living in his mental prison, or analyze why he lost, shed his rules, and reach the next level of play.

I've never been to a tournament where there was a prize for the winner and another prize for the player who did many difficult moves. I've also never seen a prize for a player who played "in an innovative way." Many scrubs have strong ties to "innovation." They say "that guy didn't do anything new, so he is no good." Or "person x invented that technique and person y just stole it." Well, person y might be 100 times better than person x, but that doesn't seem to matter. When person y wins the tournament and person x is a forgotten footnote, what will the scrub say? That person y has "no skill" of course.

Depth in Games

No one has ever been as bad at anythng as this man was at being president. At least learn from your mistakes.

I've talked about how the expert player is not bound by rules of "honor" or "cheapness" and simply plays to maximize his chances of winning. When he plays against other such players, "game theory" emerges. If the game is a good one, it will become deeper and deeper and more strategic. Poorly designed games will become shallower and shallower. This is the difference between a game that lasts years (StarCraft, Street Fighter) versus one that quickly becomes boring (I won't name any names). The point is that if a game becomes "no fun" at high levels of play, then it's the game's fault, not the player's. Unfortunately, a game becoming less fun because it's poorly designed and you just losing because you're a scrub kind of look alike. You'll have to play some top players and do some soul searching to decide which is which. But if it really is the game's fault, there are plenty of other games that are excellent at a high level of play. For games that truly aren't good at a high level, the only winning move is not to play.

Boundaries of Playing to Win

There is a gray area here I feel I should point out. If an expert does anything he can to win, then does he exploit bugs in the game? The answer is a resounding yes...but not all bugs. There is a large class of bugs in video games that players don't even view as bugs. In Marvel vs. Capcom 2, for example, Iceman can launch his opponent into the air, follow him, do a few hits, then combo into his super move. During the super move he falls down below his opponent, so only about half of his super will connect. The Iceman player can use a trick, though. Just before doing the super, he can do another move, an icebeam, and cancel that move into the super. There's a bug here which causes Iceman to fall during his super at the much slower rate of his icebeam. The player actually cancels the icebeam as soon as possible--optimally as soon as 1/60th of a second after it begins. The whole point is to make Iceman fall slower during his super so he gets more hits. Is it a bug? I'm sure it is. It looks like a programming oversight to me. Would an expert player use this? Of course.

The iceman example is relatively tame. In Street Fighter Alpha2, there's a bug in which you can land the most powerful move in the game (a Custom Combo or "CC") on the opponent, even when he should be able to block it. A bug? Yes. Does it help you win? Yes. This technique became the dominant tactic of the game. The gameplay evolved around this, play went on, new strategies were developed. Those who cried cheap were simply left behind to play their own homemade version of the game with made-up rules. The one we all played had unblockable CCs, and it went on to be a great game.

But there is a limit. There is a point when the bug becomes too much. In tournaments, bugs that turn the game off, or freeze it indefinitely, or remove one of the characters from the playfield permanently are banned. Bugs so extreme that they stop gameplay are considered unfair even by non-scrubs. As are techniques that can only be performed on, say, the player-1 side of the game. Tricks in fighting games that are side-dependent (that is, they can only be performed by the 2nd player or only by the first player) are sometimes not allowed in tournaments simply because both players don't have equal access to the trick--not because the tricks are too powerful.

There are some limits to playing to win. Not sure if this is one of them.

Here's an example that shows what kind of power level is past the limit even of Playing to Win. Many versions of Street Fighter have secret characters that are only accessible through a code. Sometimes these characters are good, sometimes they're not. Occasionally, the secret characters are the best in the game, as in Marvel vs. Capcom. Big deal. That's the way that game is. Live with it. But the first version of Street Fighter to ever have a secret character was Super Turbo Street Fighter with its untouchably good Akuma. Most characters in that game cannot beat Akuma. I don't mean it's a tough match--I mean they cannot ever, ever, ever, ever win. Akuma is "broken" in that his air fireball move is something the game simply wasn't designed to handle. He's miles above the other characters, and is therefore banned in all US tournaments. But every game has a "best character" and those characters are never banned. They're just part of the game...except in Super Turbo. It's extreme examples like this that even amongst the top players, and even something that isn't a bug, but was put in on purpose by the game designers, the community as a whole has unanimously decided to make the rule: "don't play Akuma in serious matches."

Sometimes players from other gaming communities don't understand the Akuma example. "Would not a truly committed player play Akuma anyway?" they ask. Akuma is a boss character, never meant to be played on even ground with the other characters. He's only accessible via an annoying, long code. Akuma is not like a tower in an RTS that is accidentally too powerful or a gun in an FPS that does too much damage. Akuma is a god-mode that can't coexist with the rest of the game. In this extreme case, the community's only choices were to ban or to abandon the game because of a secret character that takes really long to even select. They chose to ban the secret character and play the remaining good game. If you are playing to win, you should play the game everyone else is playing, not the home-made Akuma vs. Akuma game that no one plays.

My Attitude and Adenosine Triphosphate

I've been talking down to the scrub a lot in this article. I'd like to say for the record that I'm not calling the scrub stupid, nor did I even coin that term in the first place. I'm not saying he can never improve. I am saying that he's naive and that he'll be trapped in scrubdom, whether he realizes it or not, as long as he chooses to live in the mental construct of rules he himself constructed. Is it harsh to call scrubs naive? After all, the vast majority of the world is scrubs. I'd say by the definition I've classified 99.9% of the world's population as scrubs. Seriously. All that means is that 99.9% of the world doesn't know what it's like to play competitive games on a high level. It means that they are naive of these concepts. I really have no trouble saying that since we're talking about experience-driven knowledge here that most people on Earth happen not to have. I also know that 99.9% of the world (including me) doesn't know how the citric acid cycle and cellular respiration create approximately 30 ATP molecules per cycle. It's specialized knowledge of which I am unaware, just as many are unaware of competitive games.

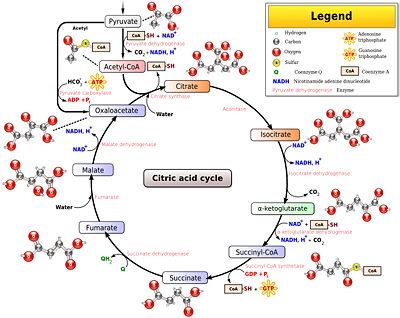

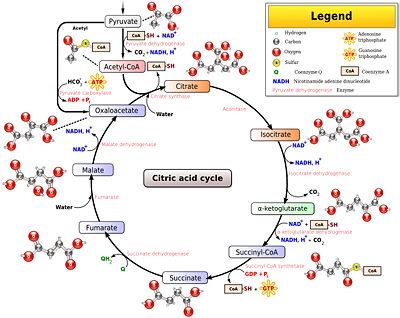

Not everyone has to know every subject. This chart is for biologists and Playing to Win is for those who want to win tournaments.

In the end, playing to win ends up accomplishing much more than just winning. Playing to win is how one improves. Continuous self-improvement is what all of this is really about, anyway. I submit that ultimate goal of the "playing to win" mindset is ironically not just to win...but to improve. So practice, improve, play with discipline, and Play to Win.

--Sirlin

I wrote this article many years ago. It was so widely quoted and valuable to so many that I spent two years writing the book Playing to Win. The book is far more polished than these articles, better organized, and covers many, many additional topics not found on my site. If you have any interest in the process of self-improvement through competitive games, the book will serve you better than the articles.

Playing to Win, Part 1

Playing to win is the most important and most widely misunderstood concept in all of competitive games. The sad irony is that those who do not already understand the implications I'm about to spell out will probably not believe them to be true at all. In fact, if I were to send this article back in time to my earlier self, even I would not believe it. Apparently, these concepts are something one must come to learn through experience, though I hope at least some of you will take my word for it.

Introducing...the Scrub

In the world of Street Fighter competition, there is a word for players who aren't good: "scrub." Everyone begins as a scrub---it takes time to learn the game to get to a point where you know what you're doing. There is the mistaken notion, though, that by merely continuing to play or "learn" the game, that one can become a top player. In reality, the "scrub" has many more mental obstacles to overcome than anything actually going on during the game. The scrub has lost the game even before it starts. He's lost the game before he's chosen his character. He's lost the game even before the decision of which game is to be played has been made. His problem? He does not play to win.

This dog may be playing poorly, but at least he still has his nonsensical internal code of honor.

The scrub would take great issue with this statement for he usually believes that he is playing to win, but he is bound up by an intricate construct of fictitious rules that prevent him from ever truly competing. These made-up rules vary from game to game, of course, but their character remains constant. In Street Fighter, for example, the scrub labels a wide variety of tactics and situations "cheap." So-called "cheapness" is truly the mantra of the scrub. Performing a throw on someone often called cheap. A throw is a special kind of move that grabs an opponent and damages him, even when the opponent is defending against all other kinds of attacks. The entire purpose of the throw is to be able to damage an opponent who sits and blocks and doesn't attack. As far as the game is concerned, throwing is an integral part of the design--it's meant to be there--yet the scrub has constructed his own set of principles in his mind that state he should be totally impervious to all attacks while blocking. The scrub thinks of blocking as a kind of magic shield which will protect him indefinitely. Why? Exploring the reasoning is futile since the notion is ridiculous from the start.

You're not going to see a classic scrub throw his opponent 5 times in a row. But why not? What if doing so is strategically the sequence of moves that optimize his chances of winning? Here we've encountered our first clash: the scrub is only willing to play to win within his own made-up mental set of rules. These rules can be staggeringly arbitrary. If you beat a scrub by throwing projectile attacks at him, keeping your distance and preventing him from getting near you...that's cheap. If you throw him repeatedly, that's cheap, too. We've covered that one. If you sit in block for 50 seconds doing no moves, that's cheap. Nearly anything you do that ends up making you win is a prime candidate for being called cheap.

Doing one move or sequence over and over and over is another great way to get called cheap. This goes right to the heart of the matter: why can the scrub not defeat something so obvious and telegraphed as a single move done over and over? Is he such a poor player that he can't counter that move? And if the move is, for whatever reason, extremely difficult to counter, then wouldn't I be a fool for not using that move? The first step in becoming a top player is the realization that playing to win means doing whatever most increases your chances of winning. The game knows no rules of "honor" or of "cheapness." The game only knows winning and losing.

A common call of the scrub is to cry that the kind of play in which ones tries to win at all costs is "boring" or "not fun." Let's consider two groups of players: a group of good players and a group of scrubs. The scrubs will play "for fun" and not explore the extremities of the game. They won't find the most effective tactics and abuse them mercilessly. The good players will. The good players will find incredibly overpowering tactics and patterns. As they play the game more, they'll be forced to find counters to those tactics. The vast majority of tactics that at first appear unbeatable end up having counters, though they are often quite esoteric and difficult to discover. The counter tactic prevents the first player from doing the tactic, but the first player can then use a counter to the counter. The second player is now afraid to use his counter and he's again vulnerable to the original overpowering tactic. (See my article on Yomi layer 3 for much more on that.)

Notice that the good players are reaching higher and higher levels of play. They found the "cheap stuff" and abused it. They know how to stop the cheap stuff. They know how to stop the other guy from stopping it so they can keep doing it. And as is quite common in competitive games, many new tactics will later be discovered that make the original cheap tactic look wholesome and fair. Often in fighting games, one character will have something so good it's unfair. Fine, let him have that. As time goes on, it will be discovered that other characters have even more powerful and unfair tactics. Each player will attempt to steer the game in the direction of his own advantages, much how grandmaster chess players attempt to steer opponents into situations in which their opponents are weak.

Sometimes I just don't know what to say.

Let's return to the group of scrubs. They don't know the first thing about all the depth I've been talking about. Their argument is basically that ignorantly mashing buttons with little regard to actual strategy is more "fun." Superficially, their argument does at least look true, since often their games will be more "wet and wild" than games between the experts, which are usually more controlled and refined. But any close examination will reveal that the experts are having a great deal of fun on a higher level than the scrub can even imagine. Throwing together some circus act of a win isn't nearly as satisfying as reading your opponent's mind to such a degree that you can counter his ever move, even his every counter.

Can you imagine what will happen when the two groups of players meet? The experts will absolutely destroy the scrubs with any number of tactics they've either never seen, or never been truly forced to counter. This is because the scrubs have not been playing the same game. The experts were playing the actual game while the scrubs were playing their own homemade variant with restricting, unwritten rules.

The scrub has still more crutches. He talks a great deal about "skill" and how he has skill whereas other players--very much including the ones who beat him flat out--do not have skill. The confusion here is what "skill" actually is. In Street Fighter, scrubs often cling to combos as a measure of skill. A combo is sequence of moves that are unblockable if the first move hits. Combos can be very elaborate and very difficult to pull off. But single moves can also take "skill," according to the scrub. The "dragon punch" or "uppercut" in Street Fighter is performed by holding the joystick toward the opponent, then down, then diagonally down and toward as the player presses a punch button. This movement must be completed within a fraction of a second, and though there is leeway, it must be executed fairly accurately. Ask any scrub and they will tell you that a dragon punch is a "skill move." Just last week I played a scrub who was actually quite good. That is, he knew the rules of the game well, he knew the character matchups well, and he knew what to do in most situations. But his web of mental rules kept him from truly playing to win. He cried cheap as I beat him with "no skill moves" while he performed many difficult dragon punches. He cried cheap when I threw him 5 times in a row asking, "is that all you know how to do? throw?" I gave him the best advice he could ever hear. I told him, "Play to win, not to do ˜difficult moves.'" This was a big moment in that scrub's life. He could either write his losses off and continue living in his mental prison, or analyze why he lost, shed his rules, and reach the next level of play.

I've never been to a tournament where there was a prize for the winner and another prize for the player who did many difficult moves. I've also never seen a prize for a player who played "in an innovative way." Many scrubs have strong ties to "innovation." They say "that guy didn't do anything new, so he is no good." Or "person x invented that technique and person y just stole it." Well, person y might be 100 times better than person x, but that doesn't seem to matter. When person y wins the tournament and person x is a forgotten footnote, what will the scrub say? That person y has "no skill" of course.

Depth in Games

No one has ever been as bad at anythng as this man was at being president. At least learn from your mistakes.

I've talked about how the expert player is not bound by rules of "honor" or "cheapness" and simply plays to maximize his chances of winning. When he plays against other such players, "game theory" emerges. If the game is a good one, it will become deeper and deeper and more strategic. Poorly designed games will become shallower and shallower. This is the difference between a game that lasts years (StarCraft, Street Fighter) versus one that quickly becomes boring (I won't name any names). The point is that if a game becomes "no fun" at high levels of play, then it's the game's fault, not the player's. Unfortunately, a game becoming less fun because it's poorly designed and you just losing because you're a scrub kind of look alike. You'll have to play some top players and do some soul searching to decide which is which. But if it really is the game's fault, there are plenty of other games that are excellent at a high level of play. For games that truly aren't good at a high level, the only winning move is not to play.

Boundaries of Playing to Win

There is a gray area here I feel I should point out. If an expert does anything he can to win, then does he exploit bugs in the game? The answer is a resounding yes...but not all bugs. There is a large class of bugs in video games that players don't even view as bugs. In Marvel vs. Capcom 2, for example, Iceman can launch his opponent into the air, follow him, do a few hits, then combo into his super move. During the super move he falls down below his opponent, so only about half of his super will connect. The Iceman player can use a trick, though. Just before doing the super, he can do another move, an icebeam, and cancel that move into the super. There's a bug here which causes Iceman to fall during his super at the much slower rate of his icebeam. The player actually cancels the icebeam as soon as possible--optimally as soon as 1/60th of a second after it begins. The whole point is to make Iceman fall slower during his super so he gets more hits. Is it a bug? I'm sure it is. It looks like a programming oversight to me. Would an expert player use this? Of course.

The iceman example is relatively tame. In Street Fighter Alpha2, there's a bug in which you can land the most powerful move in the game (a Custom Combo or "CC") on the opponent, even when he should be able to block it. A bug? Yes. Does it help you win? Yes. This technique became the dominant tactic of the game. The gameplay evolved around this, play went on, new strategies were developed. Those who cried cheap were simply left behind to play their own homemade version of the game with made-up rules. The one we all played had unblockable CCs, and it went on to be a great game.

But there is a limit. There is a point when the bug becomes too much. In tournaments, bugs that turn the game off, or freeze it indefinitely, or remove one of the characters from the playfield permanently are banned. Bugs so extreme that they stop gameplay are considered unfair even by non-scrubs. As are techniques that can only be performed on, say, the player-1 side of the game. Tricks in fighting games that are side-dependent (that is, they can only be performed by the 2nd player or only by the first player) are sometimes not allowed in tournaments simply because both players don't have equal access to the trick--not because the tricks are too powerful.

There are some limits to playing to win. Not sure if this is one of them.

Here's an example that shows what kind of power level is past the limit even of Playing to Win. Many versions of Street Fighter have secret characters that are only accessible through a code. Sometimes these characters are good, sometimes they're not. Occasionally, the secret characters are the best in the game, as in Marvel vs. Capcom. Big deal. That's the way that game is. Live with it. But the first version of Street Fighter to ever have a secret character was Super Turbo Street Fighter with its untouchably good Akuma. Most characters in that game cannot beat Akuma. I don't mean it's a tough match--I mean they cannot ever, ever, ever, ever win. Akuma is "broken" in that his air fireball move is something the game simply wasn't designed to handle. He's miles above the other characters, and is therefore banned in all US tournaments. But every game has a "best character" and those characters are never banned. They're just part of the game...except in Super Turbo. It's extreme examples like this that even amongst the top players, and even something that isn't a bug, but was put in on purpose by the game designers, the community as a whole has unanimously decided to make the rule: "don't play Akuma in serious matches."

Sometimes players from other gaming communities don't understand the Akuma example. "Would not a truly committed player play Akuma anyway?" they ask. Akuma is a boss character, never meant to be played on even ground with the other characters. He's only accessible via an annoying, long code. Akuma is not like a tower in an RTS that is accidentally too powerful or a gun in an FPS that does too much damage. Akuma is a god-mode that can't coexist with the rest of the game. In this extreme case, the community's only choices were to ban or to abandon the game because of a secret character that takes really long to even select. They chose to ban the secret character and play the remaining good game. If you are playing to win, you should play the game everyone else is playing, not the home-made Akuma vs. Akuma game that no one plays.

My Attitude and Adenosine Triphosphate

I've been talking down to the scrub a lot in this article. I'd like to say for the record that I'm not calling the scrub stupid, nor did I even coin that term in the first place. I'm not saying he can never improve. I am saying that he's naive and that he'll be trapped in scrubdom, whether he realizes it or not, as long as he chooses to live in the mental construct of rules he himself constructed. Is it harsh to call scrubs naive? After all, the vast majority of the world is scrubs. I'd say by the definition I've classified 99.9% of the world's population as scrubs. Seriously. All that means is that 99.9% of the world doesn't know what it's like to play competitive games on a high level. It means that they are naive of these concepts. I really have no trouble saying that since we're talking about experience-driven knowledge here that most people on Earth happen not to have. I also know that 99.9% of the world (including me) doesn't know how the citric acid cycle and cellular respiration create approximately 30 ATP molecules per cycle. It's specialized knowledge of which I am unaware, just as many are unaware of competitive games.

Not everyone has to know every subject. This chart is for biologists and Playing to Win is for those who want to win tournaments.

In the end, playing to win ends up accomplishing much more than just winning. Playing to win is how one improves. Continuous self-improvement is what all of this is really about, anyway. I submit that ultimate goal of the "playing to win" mindset is ironically not just to win...but to improve. So practice, improve, play with discipline, and Play to Win.

--Sirlin